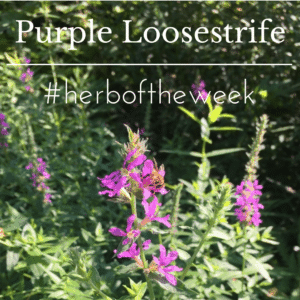

Purple Loosestrife: Herb of the Week

Purple loosestrife, Lythrum salicaria, is an under-appreciated herb, and it’s been villianized with the tag “invasive”. That label in general is really problematic for me, because plants aren’t native to locations, they’re native to growing conditions: if we change the conditions, the plants will change too! A great book on this topic is Where Do Camels Belong, by Ken Thompson.

Purple loosestrife, Lythrum salicaria, is an under-appreciated herb, and it’s been villianized with the tag “invasive”. That label in general is really problematic for me, because plants aren’t native to locations, they’re native to growing conditions: if we change the conditions, the plants will change too! A great book on this topic is Where Do Camels Belong, by Ken Thompson.

In places where the growing conditions are healthy, I have not seen loosestrife become “invasive” – it stays fairly well balanced. But in unhealthy places, it thrives. Part of the reason is that it’s doing a job: loosestrife is one of our pollution remediator plants! Purple loosestrife can actually remove PCBs from contaminated water and soil, and in fact, they did a great study on its efficacy on the Hudson River – with significant success. Plus, loosestrife can absorb excess phosphorus and nitrogen from agricultural runoff as well. That alone is enough to endear purple loosestrife, in my mind, but there’s so much more to love:

Loosestrife has a long history of medicinal use – even Dioscorides wrote about it. At that time, loosestrife was valued for its astringent qualities, especially for stopping bleeding. In more modern times, Maud Grieve wrote about loosestrife as superior to eyebright for problems in the eyes, and it has a European history of use for everything from diarrhea to typhus to sore throats. We work with loosestrife most commonly as a respiratory plant for winter illness, but also as an antifungal. That action was found quite by coincidence, actually – we were on a trip somewhere and my daughter was suffering some athelete’s foot. We didn’t have a lot of herbs with us, but we did have a tincture that had been marketed as a throat spray, with usnea and loosestrife. We used that to great success and initially attributed it to the usnea, but later discovered that usnea alone had nowhere near the anti-fungal action that the two together had. We’ve since combined the two or worked with loosestrife alone for athlete’s foot on many occasions, and we keep it on hand always.

Loosestrife has a long history of medicinal use – even Dioscorides wrote about it. At that time, loosestrife was valued for its astringent qualities, especially for stopping bleeding. In more modern times, Maud Grieve wrote about loosestrife as superior to eyebright for problems in the eyes, and it has a European history of use for everything from diarrhea to typhus to sore throats. We work with loosestrife most commonly as a respiratory plant for winter illness, but also as an antifungal. That action was found quite by coincidence, actually – we were on a trip somewhere and my daughter was suffering some athelete’s foot. We didn’t have a lot of herbs with us, but we did have a tincture that had been marketed as a throat spray, with usnea and loosestrife. We used that to great success and initially attributed it to the usnea, but later discovered that usnea alone had nowhere near the anti-fungal action that the two together had. We’ve since combined the two or worked with loosestrife alone for athlete’s foot on many occasions, and we keep it on hand always.

Loosestrife also figures prominently in our winter syrup. As urban herbalists, and especially with our busy teaching schedule, it’s not always easy for us to harvest our own herbs. But every year when the loosestrife is blooming, I head to the river to gather plants for my winter syrup. I always include purple loosestrife, elderberries, goldenrod, and sumac as my base, and then each year I work from there depending on what plants are the strongest and most abundant. Usually that includes boneset, blue vervain, nettle, plantain, yarrow, and catnip, at the least, and often I will add in some ground ivy tincture made earlier in the year (ground ivy is another one of the plants that we always harvest fresh), and some fresh baby ginger from one of our local farms, as well. Usually when I make tinctures, I tincture everything separately, which makes it easier to use that tincture to formulate in different ways for different people. But when it comes to the winter syrup, I like to tincture everything together in the same jar: just like cooking, I like the herbs to have a while to get good and friendly! I come home with my basket full, stuff it all together in a very large jar, and cover it with vodka. It macerates until the first time someone in the family gets sick – usually a month or two – then I strain it and add honey and it’s ready to go. Ideally, the honey is elderberry and loosestrife infused as well – all parts of this syrup are medicine!

Loosestrife also figures prominently in our winter syrup. As urban herbalists, and especially with our busy teaching schedule, it’s not always easy for us to harvest our own herbs. But every year when the loosestrife is blooming, I head to the river to gather plants for my winter syrup. I always include purple loosestrife, elderberries, goldenrod, and sumac as my base, and then each year I work from there depending on what plants are the strongest and most abundant. Usually that includes boneset, blue vervain, nettle, plantain, yarrow, and catnip, at the least, and often I will add in some ground ivy tincture made earlier in the year (ground ivy is another one of the plants that we always harvest fresh), and some fresh baby ginger from one of our local farms, as well. Usually when I make tinctures, I tincture everything separately, which makes it easier to use that tincture to formulate in different ways for different people. But when it comes to the winter syrup, I like to tincture everything together in the same jar: just like cooking, I like the herbs to have a while to get good and friendly! I come home with my basket full, stuff it all together in a very large jar, and cover it with vodka. It macerates until the first time someone in the family gets sick – usually a month or two – then I strain it and add honey and it’s ready to go. Ideally, the honey is elderberry and loosestrife infused as well – all parts of this syrup are medicine!

Bees also love loosestrife! It’s a pollinator species – and not just for honeybees, but for our native pollinators too! Loosestrife has been favored by American beekeepers since the 1800s, and in fact then, it was so common that botanists initially thought it was a native plant. Here in Massachusettes, attempts to eradicate loosestrife have seriously jeopardized bee populations, according to the Middlesex Beekeepers Association, because the pollinators depend on these late-season blossoms to make enough food to get through the winter. Where they are eradicating loosestrife, no native plants are growing in its place, so the space is being filled with another invasive, but one that doesn’t flower – phragmites.

Issues around invasiveness are complicated, but loosestrife is such a plant in service – to the soil and the pollinators and even the humans: and in areas where it is growing in great abundance, we can feel grateful, because that means we can harvest abundantly!

Issues around invasiveness are complicated, but loosestrife is such a plant in service – to the soil and the pollinators and even the humans: and in areas where it is growing in great abundance, we can feel grateful, because that means we can harvest abundantly!

What’s your favorite way to work with loosestrife?

#herboftheweek

3 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Join our newsletter for more herby goodness!

Get our newsletter delivered right to your inbox. You'll be first to hear about free mini-courses, podcast episodes, and other goodies about holistic herbalism.

[…] 157. Commonwealth Herbs. “Purple Loosestrife, herb of the week.” […]

[…] discussed include: loosestrife, elderberry, ground ivy, mullein, boneset, sumac, goldenrod, st john’s wort, japanese […]

[…] (for an interesting perspective on this plant, feel free to check out the following link: https://commonwealthherbs.com/herb-of-the-week-purple-loosestrife/ ) […]